When I was around ten, I remember sitting on a chair while the children of our maid sat on the floor. I noticed it. It felt wrong, but also ordinary. That’s just how things were. No one questioned it, and neither did I, at least not out loud.

Once, I tried to play with those kids. Someone pulled me back. “Don’t play with those people” I was told. I don’t remember who said it. It could have been my mother. Or my grandmother. What stayed with me was that word: those people. I didn’t protest. I accepted the rule, even if part of me felt unsettled. And like most children, I moved on. That small discomfort disappeared into the rhythm of daily life.

Years later, preparing for engineering entrance exams, I saw a different kind of division this time on a printed list. I had scored higher than several classmates, yet they were getting into better colleges through what was marked as a “reserved category.” I felt frustrated. I believed I had earned something and that it had been taken from me. But I didn’t rage. I swallowed it. Told myself this was just how things worked. I forgot the discomfort again, or buried it deep enough to believe I had.

The first real crack came much later, at my first job. A colleague, a woman from a Dalit background, offered me some food. I said yes without a second thought. Then she asked me my caste. I hesitated, but answered. She looked genuinely surprised. She said in her hometown most upper-caste people wouldn’t have eaten food she touched.

I didn’t know what to say. I think I said something dismissive, like “In cities caste doesn’t matter”. Looking back, I realize I didn’t even know what “Dalit” meant then. The word never appeared in any textbook I read. Caste had been flattened into acronyms SC, ST, OBC stripped of history, pain, and agency. I had learned to see caste as a bureaucratic category, not a social reality.

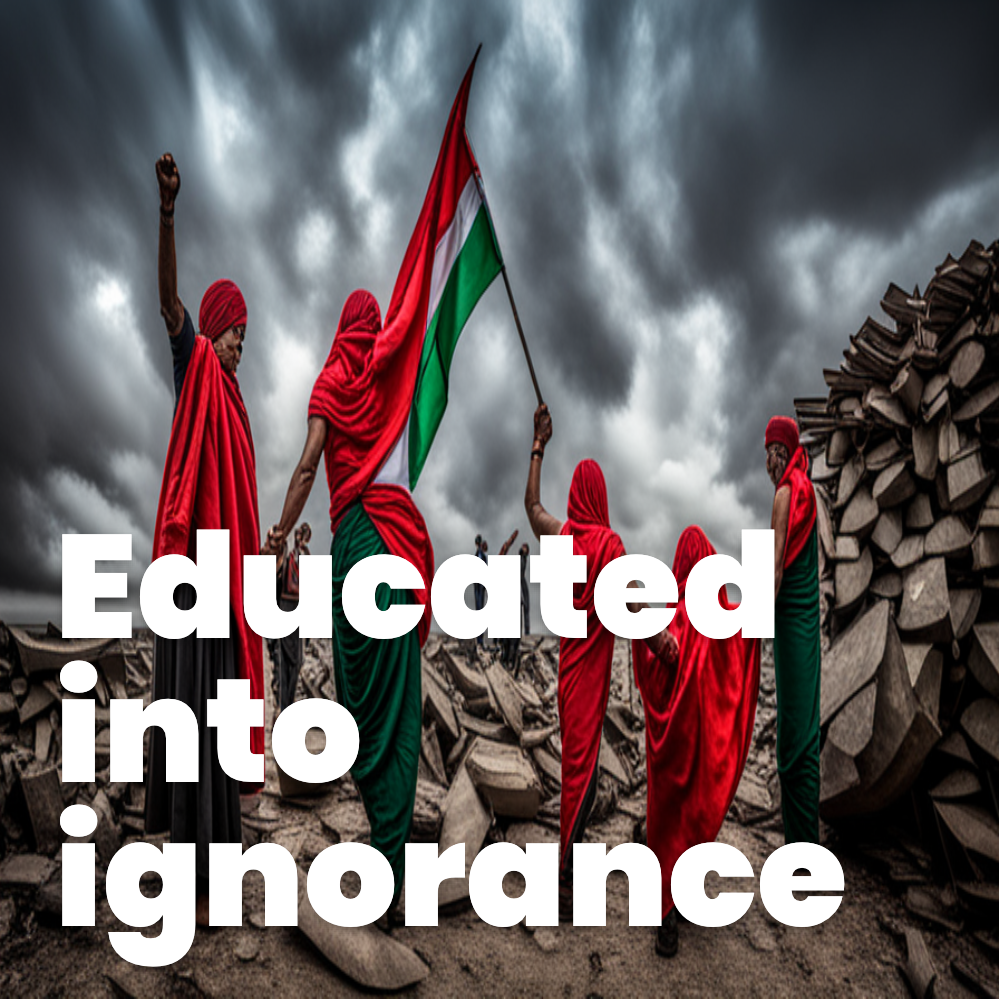

I couldn’t tell who was Dalit, and more importantly, I hadn’t needed to. Last names meant little to me because caste had never threatened me. I was educated in a system that taught me to be functionally ignorant of caste while benefiting from it. That wasn’t an oversight. It was the design.

Back then, I still equated caste with poverty. I couldn’t see how caste operated separately from wealth, how it could mark someone for life regardless of how much they earned or how far they had come.

That changed slowly, and not in a moment of epiphany. Moving to the U.S. created a new kind of dissonance. I met people who spoke openly about race and privilege. Some of them stood up for minorities not just in theory, but in practice. They read, listened, questioned themselves. Their solidarity wasn’t perfect, but it was often active. That was unfamiliar.

At the same time, I also began to notice what it meant to be invisible. And that was new for me. In meetings, I rehearsed my words before speaking. I noticed how people responded more to my accent than to my content. I thought it was my problem my confidence, my delivery. But slowly I saw it wasn’t just about me. It was structural.

Even highly educated or rich Indians abroad weren’t exempt. They also faced microaggressions, condescension, tokenism. It made me think again about merit. I used to believe in it. But now I saw how easily merit collapses into familiarity, how often it’s just a story people tell to justify power.

I started remembering things I had brushed off. The two lines in temples. The jokes and slurs chapri, ghati, kurubi. I had laughed at them. Maybe even repeated them. I never once asked who they were aimed at. I never had to.

And that’s the point. I never had to.

I started listening to Dalit writers and thinkers. I attended unlearning workshops. I read books by Ambedkar. I realized I was decades late. The words had always been there. I just hadn’t been taught to hear them. I had been educated to ignore them.

The system that once felt like background noise now revealed itself as architecture. What I had called “normal” had a design. It had builders. It had enforcers. And I had been both a beneficiary and a silent participant.

I don’t tell this story to frame myself as enlightened. I’m still unlearning. Still catching myself. But what I once dismissed as isolated discomforts, I now recognize as evidence of a deeper structure. One that shaped me, protected me, and demanded only one thing in return: silence.

And silence is what sustains it.

Caste survives not only through violence or poverty, but through denial. Through educated people like me who were taught to see ourselves as neutral, meritocratic, untouched. But neutrality is not innocence. It’s complicity disguised as fairness.

I’ve come to believe that no policy or reform can truly change India unless caste is addressed not just in courts or quotas, but in homes, friendships, textbooks, jokes, dining tables, marriages. In how we teach children to see others. In how we confront our own pasts.

Cultural progress isn’t a byproduct of economic growth. It requires deliberate discomfort. It requires those who have benefited most from the system to finally start naming it, questioning it, and dismantling their role in it.

That’s why I’m writing this. Because the first step toward change isn’t outrage at others. It’s clarity about ourselves.

Write a comment ...